Smart investing in smart materials

Global megatrends make it more important to invest differently to benefit from opportunities in smart materials, says specialist Pieter Busscher.

Samenvatting

- Smart materials include lithium used in electric car batteries

- Other growth areas are automation, robotics and software

- Massive new markets await but ESG concerns in some countries

The materials that are replacing increasingly scarce traditional resources represent the future of commodity demand, says Busscher, portfolio manager of the RobecoSAM Smart Materials fund.

He believes that the ingenious solutions being developed for products such as electric cars will massively impact the demand for traditional commodities such as low-grade steel or oil, while creating vast new markets for minerals such as lithium to make their batteries.

“The British economist Dylan Grice said that going long on commodities is like going short on human ingenuity, and what we’re trying to do here is go long on human ingenuity with smart materials,” Busscher told a recent Sustainable Investing Forum that Robeco jointly hosted with Allianz Global Investors in Brussels.

“If you look at business cycles for traditional resources, you are usually exposed to boom and bust, with limited upside, such as for oil, where we foresee a massive shift towards electric mobility. With smart materials, we’re exposed to the longer-term solutions to resource scarcity. We focus on materials that are competitive and can gain market share from traditional materials.”

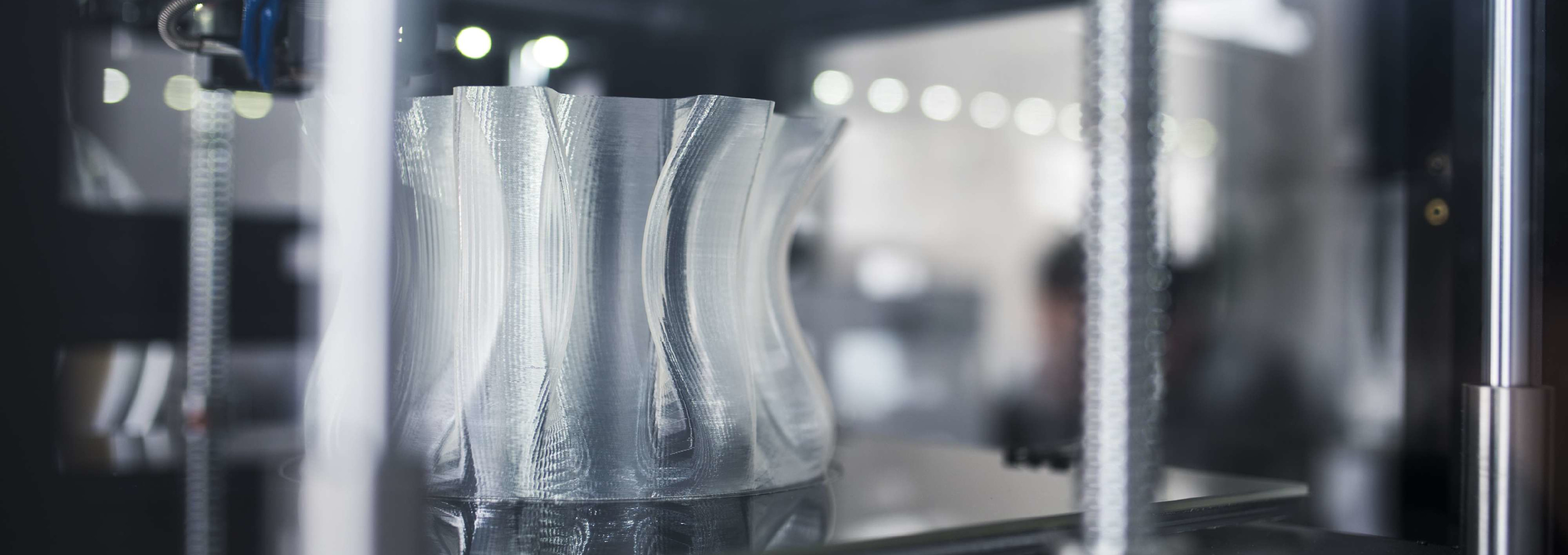

So, what are the new breed of smart materials? Busscher focuses on four main clusters: Advanced Materials and Transformational Materials, and the efficiency gains that come from new Process Technologies and Automation/Robotics.

These include themes such as fiber-lasers, artificial intelligence and 3D printing, plus the software needed to power new technologies and make new products. The market for fiber-lasers, which replace cutting and welding in industrial applications, is expected to almost double in size from about USD 3.5 billion in 2012 to USD 6.5 billion by 2020. They are about 20 times more efficient than conventional lasers and require no maintenance, enabling the production of new materials such as high-strength steel in cars.

Electric vehicles represent perhaps the biggest transformational change in modern industrial production, accounting for 10% of the 80-90 million new vehicles that will be made in 2020. China is the world’s largest market for both supply and demand – partly driven by a need to combat chronic air pollution – with more than 350,000 purchased in 2016, or more than double the number sold in the US. And while there has been much fanfare surrounding Western ‘star names’ like Tesla, its production levels are dwarfed by Chinese carmakers who were responsible for 43% all electric vehicles made in 2017.

The lightweight content of cars is set to rise from 29% to 67%.

Source: McKinsey, Robeco

This has created a whole new market for the minerals used in making electric car batteries, which in the case of a Chevy Bolt or Opel Ampera E contain 53 kilograms of lithium and 24 kg of cobalt. An electric vehicle also needs to be much lighter to maximize its range. Subsequently, the lightweight material content is expected to rise from 29% of an average car to 67% by 2030.

Ontvang de nieuwste inzichten

Meld je aan voor onze nieuwsbrief voor beleggingsupdates en deskundige analyses.

Electric Avenue

“Demand for electric cars can only grow: in Europe, we have some ambitious CO2 emissions targets coming into effect in 2021, while China has a quota of having 10% of electric cars on the roads by 2019,” says Busscher. “We’re seeing countries such as the UK and France banning gasoline engines; Norway is even more aggressive with a 2025 deadline. We may soon be looking at the traditional vehicles market as stranded assets.”

“The subsidies for electric vehicles are receding as the cost of making them has come down, and we’re looking now at a period of 2020-2021 where they will become competitive on a mainstream basis, and will win market share as they get cheaper. We could compare this to the change from horse to car at the beginning of the 20th century.”

Lithium mining areas: some have ESG issues

Source: Bloomberg.

The lithium demand from transportation is growing at over 30% a year, which has meant a traditionally slow growth industry is now exposed to sustainability issues. Incremental supply is now coming from previously untapped sources in Latin America, while half the world’s cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo. Problems include environmental damage from mining operations and the waste that it generates, combined with poor or even dangerous working conditions.

“Supply is coming from new geographies that don’t have mining frameworks that are as well established as those traditional mining countries, and that can present some concerns,” says Busscher. “A lot of production growth at the moment is in the so-called lithium triangle between Bolivia, Argentina and Chile, where we’re interacting with the mining companies to make sure standards are met.”

Smart Materials D EUR

- Performance 3y (31-12)

- 7,29%

- morningstar (31-12)

- SFDR (31-12)

- Article 9

- Dividenduitkerend (31-12)

- No

- Actuele koers (5-2)

- 398,51

Reinventing commodity markets

Busscher says new materials are slowly reinventing how commodities are valued in markets, making it essential to review investment strategies now. “The traditional approach to investing in materials is to invest directly in commodities or commodity stocks, based on the assumption that with limited supply and increasing demand, the price of commodities should rise,” he says.

“Yet real commodity prices have declined steadily, suggesting that natural resources have not become more scarce in the economic sense of the term. This is because free market forces and human ingenuity have generally led to technological breakthroughs and the development of substitutes that have enabled us to grow despite resource scarcity.”

“We have secular, long-term trends in place that are powered by human’s unique ability to continually innovate. As we deplete our stock of finite resources and environmental issues intensify, banking on human ingenuity is a promising investment approach of the future for the materials sector and beyond.”