Running a tight chip – is there relief in sight for semiconductor supplies?

Two years on, the global economy still grapples with a severe chip shortage, with no immediate end in sight.

まとめ

- Industry caught off guard by booming pandemic demand

- Mid- to low-end consumer products (from autos to washers) hardest hit

- Smart energy holdings well positioned to benefit from chip squeeze

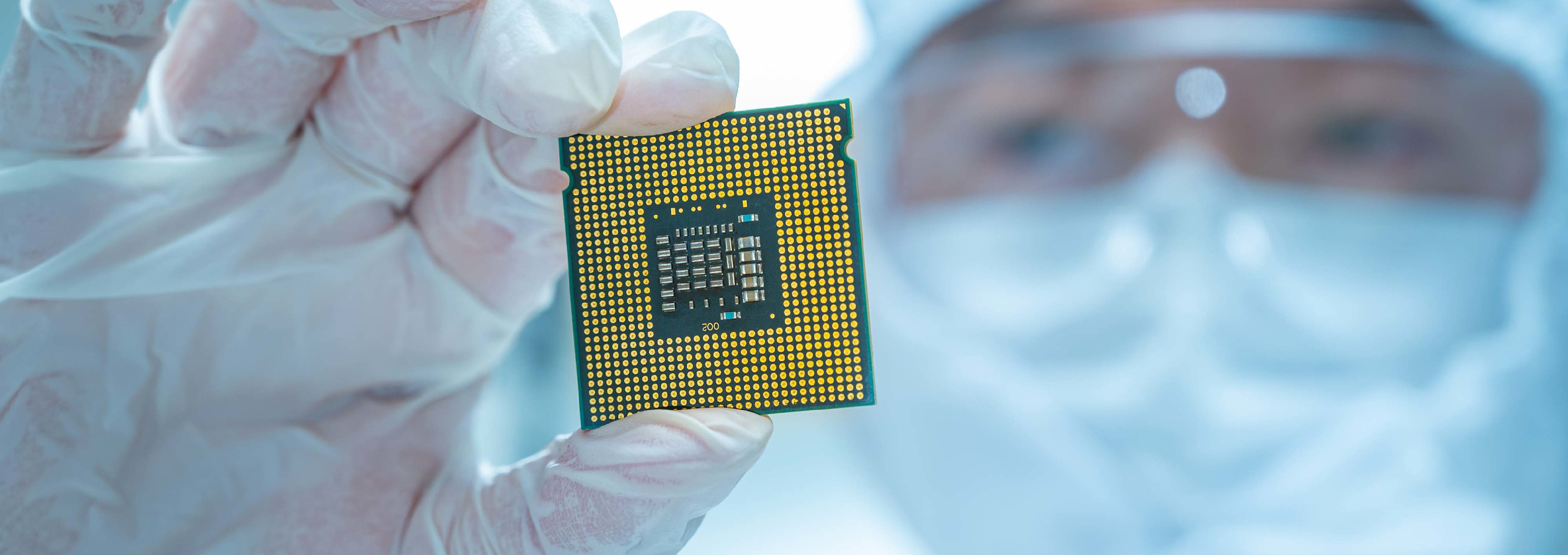

Semiconductor chips are necessary for all modern electronics – from smartphones to laptops. They are also at the core of many less sophisticated white goods like dishwashers, heating systems and point-of-sale devices.

The most prominent victims are automakers that have been forced to halt production in recent months, losing an estimated USD 210bn of sales in 2021.1 The shortage has also affected other industries like medical devices, networking equipment and game consoles. More recently, even the PC and smartphone industries blamed chip shortages for lowering output targets.2 Ironically, even companies making machines to produce semiconductor chips are suffering from shortages.

One key driver for the shortage is the sheer scale of demand after the Covid crisis that many in the industry underestimated. In 2019, chip sales fell by 12%, driven by the cyclical nature of memory chips. In late 2019, however, the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) predicted global sales growth of 5.9% for 2020 and 6.3% for 2021 – even before the pandemic hit the mainstream economy.3 Many market participants reacted to the Covid crisis by taking out their recession playbooks – cutting orders and reducing inventory. However, thanks to lockdown measures and government stimuli, the Covid crisis led to an unpredicted outcome – consumers and companies increased spending on digital goods and infrastructure. Accordingly, SIA saw semiconductor sales grow by 29.7% from August 2020 to August 2021, driven by demand for 5G phones and cloud infrastructure, but also in classic electronic goods like PCs, TVs and webcams.4

The Covid effect came in combination with secular trends in home appliances and cars becoming smarter, equipped with more chips than in the past (e.g., an electric vehicle uses roughly double the semiconductor content of a regular car). The digitalization of the economy in general (e.g., the shift to e-commerce and digital work) is also fueling a constant increase in the demand for chips. Unfortunately, even geopolitical actions had their impact: US imposed sanctions on Chinese technology companies (e.g., Huawei) in 2019 led to Chinese manufacturers hoarding chips to ensure supply.5

The chip industry has historically suffered from “boom-and-bust” cycles as well as “double ordering,” where clients buy more chips than needed. As supply and demand normalized and tightness in the chip market abated, demand dramatically declined. Based on past experience, most players in the semiconductor market were understandably reluctant to invest into more capacity to satisfy temporarily high demand without strong, long-term customer commitments. Even though TSMC, Intel and Samsung did eventually increase their investment in new fabs, these modern semiconductor plants cost more than USD 10bn each and take years to build as chip complexity increases.6 As a result, most invested capacity will only be available in 2023 or even 2024 – as most equipment makers have seen lead times stretch to more than 52 weeks (double the usual).

Highest margins win capacity

Capacity is generally only added at the leading edge, meaning fabs are built to produce the most modern semiconductors, as only these chips carry the profit margins required to amortize the high fixed capital costs. Over time, as chip technology gets commoditized, older chip designs (like those for less sophisticated automotive applications) also benefit from moving into this higher-end capacity. However, this is a long process and provides no immediate solution. For the time being, we currently face the unusual situation of legacy chips (40nm to 90nm nodes) used for automotive and white goods, feeling the squeeze, whereas capacity is mainly expanding for bleeding-edge nodes (5nm and 7nm).

Accordingly, chip manufacturers have reacted with selective price increases that reflect the tightness of the market at different node levels. Figure 1 illustrates price hiking mechanism of leading fabs across different nodes for 2021 and 2022.7

Figure 1 | Price increases for lower-end (legacy) chips

Source: Counterpoint Technology Research, Robeco

As Figure 1 demonstrates, price increases will continue into 2022, indicating continued imbalance of supply and demand for legacy chips. Therefore, we are not optimistic that the tightness in the semiconductor market will be resolved as quickly as some industry participants and investors expect. The pain might just shift to other areas of the market.

It may get worse

Several risks also loom in the highly consolidated global semiconductor supply chain. A Corona-driven lockdown in Xi’an, a leading manufacturing hub in China that is home to many memory chip component factories, meant supplies for semiconductor leaders, Samsung and Micron, were temporarily disrupted. Moreover, a fire at ASML’s optical production site in Berlin over New Year’s Eve may also impact its customers. Incidents like these could further exacerbate supply imbalances and inflate prices.

Several large technology companies are working hard to make virtual and artificial intelligence (VR & AR) mainstream, leading to potentially huge demand for smart glasses equipped with high-powered semiconductor content. The recent stronger push for a more carbon-neutral world often means a shift from “dumb energy” such as burning fossil fuels to “smart energy” like batteries, solar cells and wind turbines, all of which make heavy use of semiconductors to control and optimize energy production, storage and distribution. However, the history of the semiconductor industry indicates that once tension is released, the bust cycle will be, once again, at play.

The Smart Energy Strategy is overweight in analogue and power semiconductors driven by strong secular trends in electric vehicles and smart grids as well as the robust economic recovery. These should help increase utilization, tighten supply, raise prices and lead to continued higher profits even given inflationary pressure. However, as these factors are priced in, the Strategy has become more selective of its semiconductor holdings.

Footnotes

1 Bloomberg, September 23, 2021,“Worsening Chip Woes to Cost Automakers $210 Billion in Sales.”

2 cnbc.com, July 29, 2021,“The global chip shortage is starting to hit the smartphone industry.”

3 Semiconductor Industry Association Report, December 3, 2019.

4 Ibid.

5 cnbc.com, September 18, 2020,“A brewing U.S.-China tech cold war rattles the semiconductor industry.”

6 Bloomberg, April 2021,“TSMC to Spend $100 Billion Over Three Years to Grow Capacity.”

7 EE Times Asia, September 2021,“TSMC Price Hike Indicates Capacity Tightness to Persist in 2022.”

重要事項

当資料は情報提供を目的として、Robeco Institutional Asset Management B.V.が作成した英文資料、もしくはその英文資料をロベコ・ジャパン株式会社が翻訳したものです。資料中の個別の金融商品の売買の勧誘や推奨等を目的とするものではありません。記載された情報は十分信頼できるものであると考えておりますが、その正確性、完全性を保証するものではありません。意見や見通しはあくまで作成日における弊社の判断に基づくものであり、今後予告なしに変更されることがあります。運用状況、市場動向、意見等は、過去の一時点あるいは過去の一定期間についてのものであり、過去の実績は将来の運用成果を保証または示唆するものではありません。また、記載された投資方針・戦略等は全ての投資家の皆様に適合するとは限りません。当資料は法律、税務、会計面での助言の提供を意図するものではありません。 ご契約に際しては、必要に応じ専門家にご相談の上、最終的なご判断はお客様ご自身でなさるようお願い致します。 運用を行う資産の評価額は、組入有価証券等の価格、金融市場の相場や金利等の変動、及び組入有価証券の発行体の財務状況による信用力等の影響を受けて変動します。また、外貨建資産に投資する場合は為替変動の影響も受けます。運用によって生じた損益は、全て投資家の皆様に帰属します。したがって投資元本や一定の運用成果が保証されているものではなく、投資元本を上回る損失を被ることがあります。弊社が行う金融商品取引業に係る手数料または報酬は、締結される契約の種類や契約資産額により異なるため、当資料において記載せず別途ご提示させて頂く場合があります。具体的な手数料または報酬の金額・計算方法につきましては弊社担当者へお問合せください。 当資料及び記載されている情報、商品に関する権利は弊社に帰属します。したがって、弊社の書面による同意なくしてその全部もしくは一部を複製またはその他の方法で配布することはご遠慮ください。 商号等: ロベコ・ジャパン株式会社 金融商品取引業者 関東財務局長(金商)第2780号 加入協会: 一般社団法人 日本投資顧問業協会